I once had a conversation with a friend about Game of Thrones that led to talking about Jesus. Or at least, it nearly did. But I bottled it.

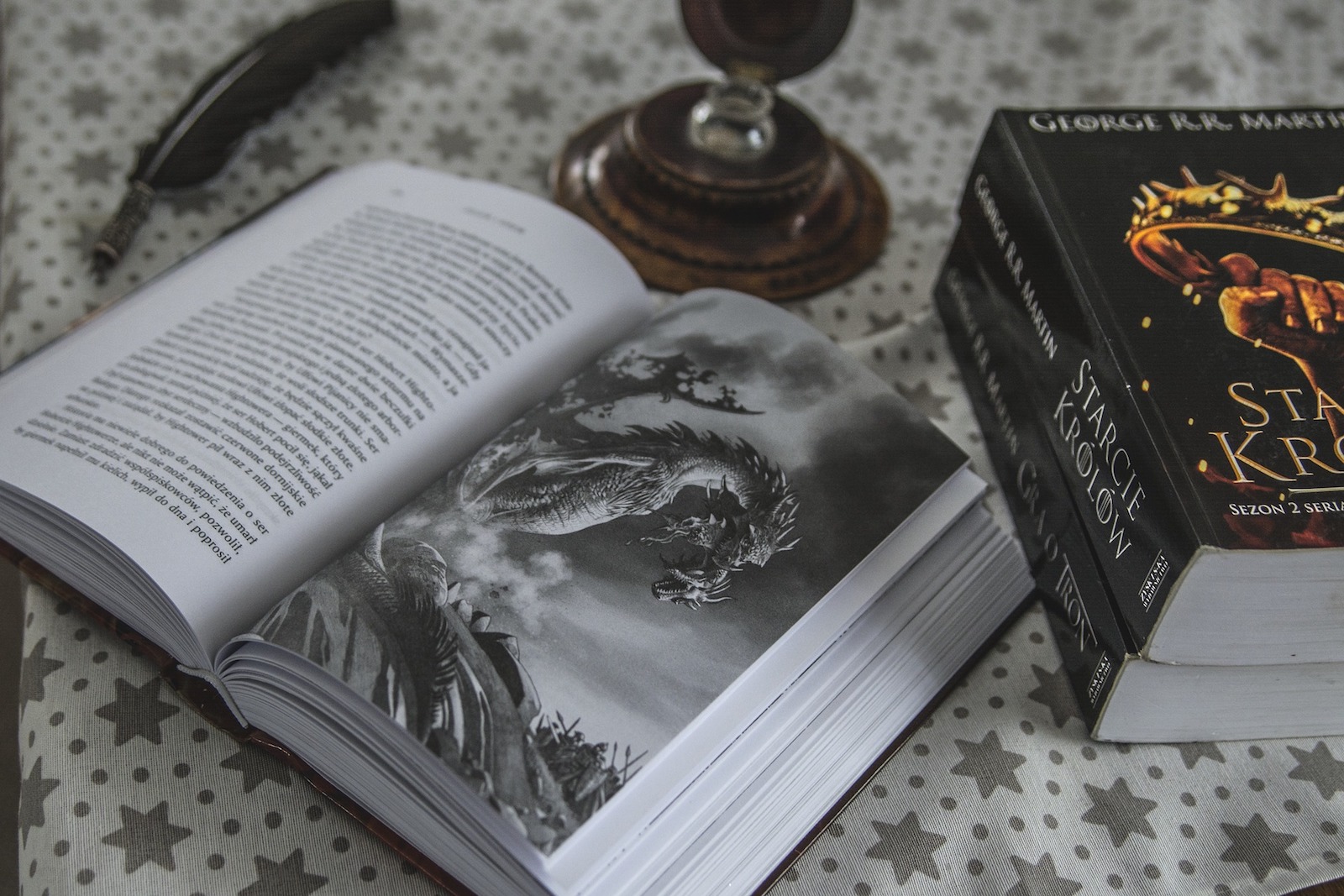

It was at the beginning of the HBO series’ immense popularity, and we were both curious. Not knowing much about it but going on a family member’s recommendation, I’d decided to read George R.R. Martin’s first book, while my friend had been watching the first episodes of the TV series. But unlike millions of other viewers and readers, we hadn’t liked it very much, and we were trying to work out why.

Enjoy culture in a way that feeds your faith and helps you share it with others.

“The thing is,” said my friend, “if you’re making up a fantasy world, you can make it with any rules you choose. So why did he make it this way?”

For her, the problem was the sexual violence that runs through both books and films. Why not choose to imagine a world in which women are valued and sex is not used to oppress?

What had struck me the most was broader: it was the pessimism of the whole thing. The endless deaths and injustices made life in the world of Westeros seem meaningless. Unlike so many other fantasy series, where the main characters miraculously escape every hostile blow and cunning plot, in Martin’s world death and misfortune take victim after victim.

In one sense I can see why. After all, in real life, death isn’t picky. Too often, it comes suddenly and unexpectedly. Allowing death to rip indiscriminately through the cast list is a way of making things more realistic.

But my friend and I agreed: if this was realism, we didn’t want it.

Looking back, I wish we had talked more about why we felt this way.

For me it was tied up in my faith. I see this world as one in which every individual is known and seen by their Creator, where injustice and oppression will not prevail, where death is not final. A world with a happy ending, announced by Jesus and won by him on the cross.

So we were right to be upset by the violence in the series; right to be discomfited by its pessimism. A world of justice and freedom is a good and godly thing to hope for.

But I think George R.R. Martin’s harsh and horrible world made us uncomfortable for another reason, too: one the author himself intended. When criticised about the series’ depiction of rape, he explained what he was trying to show: “that the true horrors of human history derive not from orcs and Dark Lords, but from ourselves.”

His words are not so different from what Jesus says in Mark 7 v 21-22: “it is from within, out of a person’s heart, that evil thoughts come—sexual immorality, theft, murder, adultery, greed, malice, deceit, lewdness, envy, slander, arrogance and folly.” All the things my friend and I disliked about Game of Thrones, in fact. The horror is there in our own hearts.

So we were wrong, too. We wanted to think that the world is better than it is.

My friend isn’t a Christian. I wish I’d told her that the horror I felt at the violence in Game of Thrones should, in reality, also be directed at my own heart. I wish I’d told her that the discomfort I felt about the pessimism in the series was that I know that, in reality, there is hope for the world.

“We need to think of the stories our culture tells us and the themes it peddles,” Dan Strange tells us in his book Plugged In. “We need to learn to identify where they are suppressing the truth, and to spot where that truth keeps “popping up” like a beach ball ... We can both confront and connect the gospel to any and every broken story.”

So, having missed my chance with Game of Thrones, I’m going to try to think that way—and speak that way—about the next blockbuster series instead. The Crown, anyone?

Whether it's TV boxsets, Instagram stories or historical novels, we all consume culture. In Plugged In, Dan Strange encourages Christians to engage with everything they watch, read and play in a positive and discerning way. He also teaches Christians how to think and speak about culture in a way that plugs in to a bigger and better reality—the story of King Jesus, and his cosmic plan for the world.