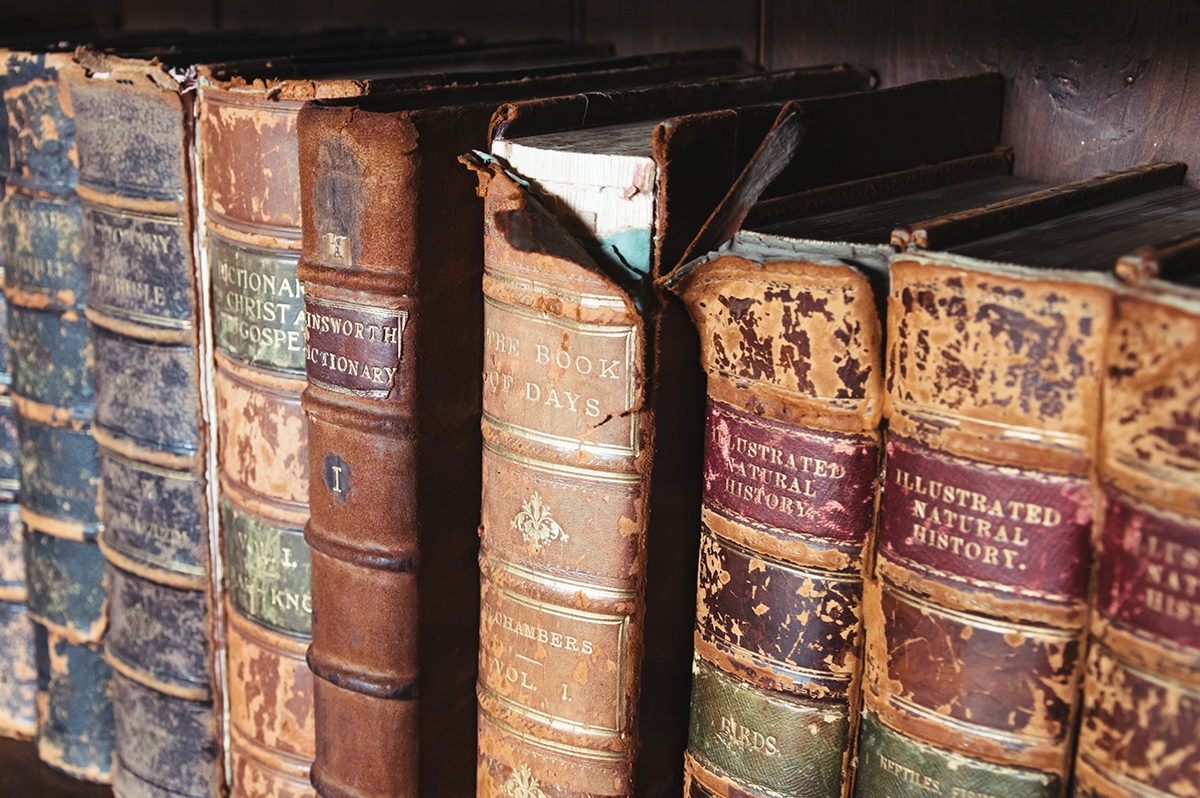

History is not just real; it is also knowable. Not fully knowable, of course. Probably less than 1% of ancient remains remain today. But 1% is enough to provide precious insight into the real lives of first-century men and women. Try this thought experiment…

Imagine people two thousand years from now digging up London and discovering 1% of the Daily Mails, 1% of the city’s statues and inscriptions, 1% of Marks & Spencer’s receipts, 1% of the Parliamentary documents from Westminster, and 1% of the lost letters in the Royal Mail’s National Returns Centre. While much of ordinary life from London 2019 would remain invisible to future historians, a great many other things could easily and reliably be known.

An exploration of the historicity of Jesus and whether he is relevant today

We would know the names of quite a few of the leaders of Great Britain, and around the world, too. We would know something of what people valued and memorialised. We would have some insight into the food people ate, how much things cost, and how Londoners generally spent their money. And from just a small selection of government legislation and private correspondence we would gain a pretty accurate picture of at least some aspects of life in 2019.

In addition to these broad-brush impressions of 21st-century London, historians of AD 4019 would have highly detailed portraits of particular individuals, some famous, some obscure. Much would be reliably said about the Prime Minister or the Queen, of course, but it would only take the chance discovery of a bundle of letters from a few individuals to be able to piece together a detailed, even intimate, account of the lives of ordinary men and women of the time.

Ancient history is just like this. It is both frustratingly incomplete and remarkably intimate. While we have formal biographical accounts of Tiberius (the second Roman emperor, reigning from 14 AD to 37 AD), for example, as well as coins and inscriptions bearing his name and titles, we do not have even one piece of personal correspondence from the emperor. And, yet, from a slightly later period we have 121 letters of Pliny the Younger (nephew of the older Pliny) to various friends and colleagues, including a good number of replies from the emperor of his time (Trajan). These are a treasure trove of insights into one Roman aristocrat’s thoughts, work, hunting trips, reading habits, holidaying, loves, hopes and fears.

To give an example closer to the home of the first Christians, we have solid general evidence that the most influential Jewish rabbi in Roman Judea was a scholar named Hillel. But sadly, we don’t have a single letter from this man who was, by all accounts, an intellectual tour de force of the movement known as the Pharisees.

By contrast, we have close to 30,000 words of correspondence from a junior Pharisee (just a few decades after Hillel) named Saul of Tarsus. He is better known as the apostle Paul, the author of numerous letters now contained in the New Testament. These letters, while chiefly read today for their theological content, offer an enormous amount of random information about first-century language, rhetoric, religion, social history, travel and customs (Jewish, Greek and Roman), as well as the inner life of one Jewish-born, Greek-educated man responsible for taking the Christian message throughout Asia Minor (Turkey), Greece, and beyond.

My new book Is Jesus History? is an attempt to explain how we know about an ancient figure like Jesus or Paul, and also something of what we know. I use the word “know” deliberately. The conclusions of history, including the history of Jesus, are known. This is why history itself used to be called a “science”, from the Latin scientia or “knowledge”. It is a straightforward fact that those specialising in this period, regardless of religious affiliation or none, agree overwhelmingly that we know a fair bit about Jesus. The conclusion of Duke University’s E.P. Sanders in his classic book The Historical Figure of Jesus would be acceptable to most secular experts in the field today:

"There are no substantial doubts about the general course of Jesus’ life: when and where he lived, approximately when and where he died, and the sort of thing that he did during his public activity."

Sanders is no friend of Christian apologetics or of theology dressed up as history. As one of the leaders of the secular approach to studying Jesus over the last 30 years, Sanders has no qualms about dismissing this or that bit of the New Testament. Yet, he rightly regards the Gospels and the letters of Paul as important human sources, crucial for a good understanding of the events in Roman Galilee and Judea in the 20s and 30s AD, the time when Tiberius reigned, when his mother Livia passed away, when Pliny (Elder) was learning to read, and when the coin around my neck was struck.

Historical events were once as real as the experiences you are having today. Indeed, they are no different from the events of yesterday. Those events are no longer here—in a sense, nothing but the immediate present is “here”—but they are solid facts of the same world we inhabit. Historical investigation is the science and art of discerning how much of those tangible events of the past can be known today.

In this timely book, Is Jesus History? historian Dr John Dickson unpacks how the field of history works, giving readers the tools to evaluate for themselves what we can confidently say about figures like the Emperor Tiberius, Alexander the Great, Pontius Pilate, and, of course, Jesus of Nazareth.